by Michelle Barbieri

Ever wondered how to reboot a propane-powered refrigerator? Flipping it upside-down is actually a viable strategy. This is the latest challenge overcome by our remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands field teams in the initial stages of the summer 2017 Assessment and Recovery Camp’s monk seal vaccination program.

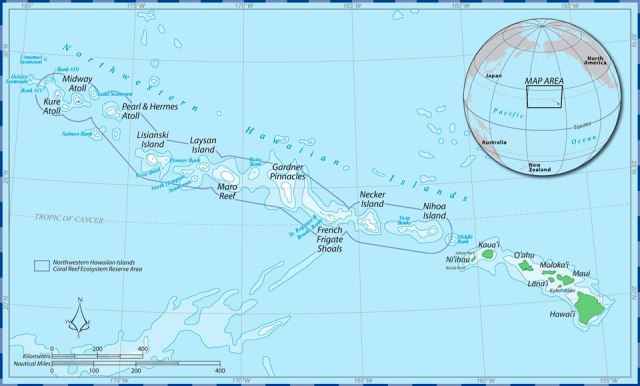

Map of the Hawaiian Archipelago with the Northwest Hawaiian Islands outlined.

Getting vaccinated for us humans usually means a quick trip to the doctor. We take our pets to the vet for their “shots.” For some wildlife, rabies vaccines are distributed in bait across the continent. But what about vaccinating marine wildlife, especially those that live in remote locations and may travel hundreds of miles? The hurdles are high, the path is uncharted, and no matter how much you plan and prepare, there are going to be times when flipping refrigerators upside-down is the vital solution.

Simple living in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands – the kitchen tent at Pearl and Hermes Reef field camp (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

The Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program’s vaccination efforts began in 2016, vaccinating seals on Oahu and Kauai against morbillivirus in order to prevent an outbreak that could be catastrophic for the species. To our knowledge, the endangered Hawaiian monk seal has never suffered from a morbillivirus outbreak, but recently, researchers have found other species of morbillivirus in Hawaii and the greater Pacific region. We know the monk seals are naïve (unexposed) to morbillivirus from decades of disease surveillance in the species. While that’s a good thing, we’d like to keep it that way! When morbillivirus outbreaks have occurred in other marine mammals, the results were rapid and deadly, killing tens of thousands of seals and dolphins in Europe and North America. With only about 1400 left in the world, the endangered population of Hawaiian monk seals can’t take such losses.

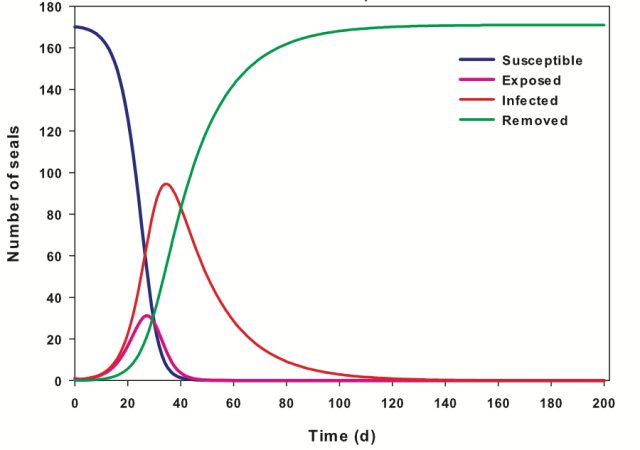

Recently, researchers developed mathematical models to estimate how an outbreak would spread if morbillivirus were introduced, say from another seal species or a dog. The results confirmed our fears–the monk seal population could be devastated. Vaccination is a proactive way to protect the monk seal, rather than waiting until the virus shows up to treat it.

What would happen in a seal population facing a rapidly spreading morbillivirus outbreak without vaccination? The red bump shows the peak of infected seals, the green line shows the rapid accumulation of seals “removed” from the susceptible seals (either after overcoming infection or succumbing to it).

Over the last 10 years, a vaccine (made for ferrets!) was evaluated for use in captive seals, including Hawaiian monk seals. After years of testing, planning, and practice, the vaccine was given to the first wild monk seals in 2016. Each seal needs two shots, about four weeks apart. Those efforts protected most of the seals around Kauai and Oahu and represented the start of the world’s first-ever species-wide vaccination program in wild marine mammals.

Now, in 2017, we are expanding the monk seal vaccination program to protect seals in the distant Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. But launching this initiative across a span of more than 1,000 miles on remote, low-lying sandy islands and atolls is an entirely unique process with a lot of logistics to figure out. We’ve had to think of everything from propane fridges to keep vaccines cold, to min-max thermometers to monitor their temperatures in the field, to PVC pipe cases to keep sand out of syringes (which we fasten into “pole syringes”). We even modified our monk seal databases to track the vaccinated seals for the rest of their lives. We also need to vaccinate a LOT of seals to make a meaningful dent in the susceptibility of the monk seal population. In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, monk seal populations are larger and denser than we’re used to in the main Hawaiian Islands. A disease would have more opportunities to jump between each seal and spread rapidly; therefore, we must vaccinate many more seals on these remote islands in order to achieve the same level of protection as the main islands.

Many seals share the beach on Nihoa Island. Denser seal populations with lots of contact between animals are common in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

For nearly two months, field staff trained and practiced safely administering injections, and are now beginning to vaccinate seals. It’s just the first week of field camps and already 12 seals received vaccines. Another 25 seals have been vaccinated at Midway Atoll during short-term staff deployments. There’s still a long way to go, but we are well on our way to protecting these precious animals against a deadly outbreak.

Vaccination mission at Laysan: Helena preps the pole syringe with a vaccine dose; Kristen sneaks up on a sleeping seal to carefully deliver a vaccine; Hope runs from another after successfully vaccinating (and surprising!) the seal. Note: a syringe on a long pole is the least intrusive way that scientists can give vaccinations to seals for their protection. It’s important to keep your distance from seals. (Photos: NOAA Fisheries)