By Shannon Coates and Mark Cotter

HICEAS Lead Acoustician and HICEAS Cetacean Observer

With the the Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey (HICEAS) of 2017 winding down, we were approached by our Cruise Leaders about writing a blog about the rough-toothed dolphin (Steno bredanensis). It’s kind of funny that we were asked to write a blog about this species, because unbeknownst to our Cruise Leaders, the rough-toothed dolphin is one of our favorite cetaceans (whales and dolphins). Not only do rough-toothed dolphins have a distinct reptilian appearance that conjures thoughts of a prehistoric animal (at least in our opinion), they also happen to be one of the smartest dolphins in the ocean. As a result, rough-toothed dolphins are one of the more easily distinguishable dolphin species and demonstrate unique and interesting behaviors.

With their gently sloping heads and large bulging eyes, we think rough-toothed dolphins look somewhat reptilian and prehistoric – a dolphin dinosaur, if you will. What do you think? Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Marie Hill

When you hear the name rough-toothed dolphin, you would be correct to assume that their teeth are a feature we can use to identify them. However, even though there are distinctive vertical ridges on their teeth, you would need to be very close to the open mouth of a rough-toothed dolphin to see this identifying trait! A more practical common name for these dolphins would take into account the very distinct appearance of their head. Rough-toothed dolphins have an unusual forehead, which slopes gently down from the blowhole all the way into the narrow rostrum (or beak) without any demarcation between the melon and the beak. The melon is a very specialized waxy-fatty organ positioned on top of the head in front of a toothed-whale’s eye that allows for the function of echolocation, a type of bio-sonar these animals can use to navigate and find prey. A good example with which to contrast the head of a rough-toothed dolphin is the head of a bottlenose dolphin, which has a distinct crease separating the melon from the short, stubby beak (from which bottlenose dolphins get their common name). Completing the unique look of the rough-toothed dolphin head are its large, bulging eyes and varying degrees of white on its lower jaw that typically get whiter with age.

The lower jaws of rough-toothed dolphins typically get whiter with age. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Michael Force

Who are you calling a slow dinosaur? Extremely intelligent, now that’s more like it! Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Carrie Sinclair

Another interesting characteristic of this species is the evolution of large appendages (pectoral flippers and dorsal fin) relative to their body size. Rough-toothed dolphins have large pectoral flippers with rounded tips, which is typical of the body plan of slower-moving cetaceans. Normally, the fastest-moving dolphin species will have smaller and pointed fins that are more suitable for high speeds and quick directional changes. This is not to say that rough-toothed dolphins are slow by any means, just in comparison to other open-ocean dolphin species. In fact, slower methodical movement better explains the behaviors we generally observe among groups of rough-toothed dolphins hunting for fish around floating debris or hanging out at the periphery of tuna schools.

Rough-toothed dolphins have been described as extremely intelligent. Cetaceans, in general, are considered one of the three peaks in brain evolution history along with primates and elephants. Rough-toothed dolphins have the highest encephalization quotient among any cetacean in the world, which is a measure of their brain size (and development of that big brain) relative to their body size. These dolphins clearly demonstrate their intelligence in their environment as they are observed hunting for food in clever ways, without relying solely on speed.

Rough-toothed dolphins generally live in fluid fission-fusion societies, where members of groups can interchange frequently, but still maintain very close social bonds with each other. Group size is generally on the smaller side, ranging from just a few animals to about 100, but these individuals can be spread out over a large distance. These smaller subgroups are likely formed with the intent of stealthily hunting for prey, which is one possible reason why they can be difficult to detect during a visual survey.

A group of rough-toothed dolphins spotted about 10 nautical miles west-northwest of Kaʻena Point on Oʻahu. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Andrea Bendlin

A primary goal of HICEAS is to estimate the size of cetacean populations in Hawaiian waters using a method known as line-transect sampling. Abundance estimates from the last HICEAS (in 2010) indicated that the rough-toothed dolphin was the most abundant species in the study area. This high abundance estimate was linked to a parameter in the estimation process that suggested that rough-toothed dolphins had the lowest probability of being detected on the trackline, given the sea conditions during the survey effort. Indeed, experienced observers have noted that rough-toothed dolphins are difficult to detect given their relatively small group sizes and subtle surfacing behavior, sometimes seeming to suddenly appear and oftentimes mixed with other species. However, researchers at the Cascadia Research Collective found that the sighting characteristics of rough-toothed dolphins around the main Hawaiian Islands were almost identical to those of bottlenose dolphins and that the resighting rates of individual rough-toothed dolphins were high enough to indicate that at least island-associated populations are not especially large. Are rough-toothed dolphins really the most abundant cetacean species around Hawaiʻi or is there something about their detectability or behavior that we’re not accounting for in our data collection or abundance estimation methodology?

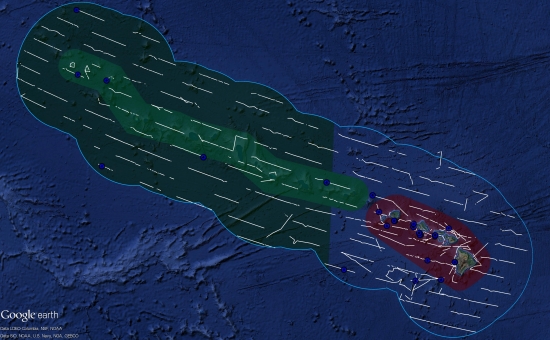

This map of the Hawaiian Islands shows all of the HICEAS 2017 survey effort (white lines), with rough-toothed dolphin sightings shown as blue circles. The red shading is a focus area around the main Hawaiian Islands, and the green shading is the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, with darker shading where the Monument was expanded in 2016.

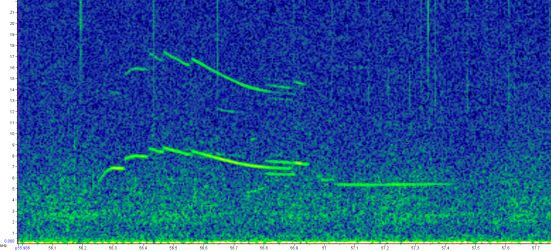

The answer may lie in acoustics. The acoustics team generally has a higher encounter rate than the cetacean observers, meaning that we often hear rough-toothed dolphins that they never saw, and we don’t have to worry about the effects of survey conditions and sneaky surfacing behavior. Acoustics may help us better understand the circumstances that lead to missed visual detections and refine our abundance estimates accordingly. Rough-toothed dolphins, like other delphinids, produce both whistles and echolocation clicks that are believed to aid in socializing (whistles) and finding food (echolocation clicks). Their vocalizations have the potential to be confused with the dolphins known as “blackfish” (e.g., killer whales, false killer whales, and pilot whales) because, like blackfish, rough-toothed dolphins produce short-duration whistles ranging from 2.5 to 10 kilohertz and clicks from 10 to 90 kilohertz. They seem to be one of the only non-blackfish species whose whistle and echolocation click frequencies overlap so closely with blackfish. What does make rough-toothed dolphins vocalizations unique from blackfish is that their whistles are simple in structure and usually have very characteristic “steps.” We do not know what has driven the evolution of this special whistle, but it helps us identify the species without needing a visual confirmation.

A spectrogram (or visual representation of sound) showing the “stepped” whistles of rough-toothed dolphins.

Have a look at the HICEAS website to find out what else we saw in the remaining days of HICEAS 2017!

All photos taken under research permit.