By Amanda Bradford, Marie Hill, and Kym Yano

PIFSC Cetacean Research Program

Once used mostly for military purposes, unmanned aircraft systems (UASs, aka drones) are becoming increasingly popular in a wide range of civilian activities. It’s hard to go outside these days without seeing a recreational drone in the air, especially here on the beaches of O’ahu. An aerial view often offers a unique and useful perspective of a particular subject, which a UAS can provide with less of a financial and human investment than a manned aircraft. The use of UAS technology to study wildlife, including cetaceans (whales and dolphins), is spreading rapidly, with the added bonus that a UAS can be less disruptive to animals than other research methods.

The PIFSC Cetacean Research Program (CRP) is tasked with providing scientific information to support the conservation of cetacean populations in the Pacific Islands. Specifically, we estimate the sizes of these populations, determine where they spend their time, and evaluate human-caused threats that may be affecting them. We are ultimately interested in the health of the populations and the individuals within them. To accomplish our research goals, we use a number of methods, including photo-identification, biopsy sampling, satellite tagging, and acoustic monitoring. Embracing the wave of UAS technology, we were very excited to add aerial photography to our toolkit because taking vertical photographs from the air gives us a way to directly investigate the health of populations and individuals. For example, we can keep track of how many females in a population are having calves and measure the body condition of individual whales and dolphins.

However, there was only one problem. No one in the CRP had a background in cetacean aerial photography or even knew how to fly a drone. We were, literally, starting from ground zero.

Learning to fly a UAS over whales did not begin on the open ocean, but instead in a grassy field. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Amanda Bradford

In the spring of 2017, we began the process of becoming UAS trained and certified, following through with both Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and NOAA requirements. We focused on working with the APH-22 hexacopter, an approved NOAA platform that has been used by other biologists to successfully collect vertical aerial photographs of cetaceans and other marine mammals. We completed all our basic requirements and some initial training work just in time for the Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey (HICEAS), which took place from July to December of 2017. We were prepared to add hexacopter operations to our suite of research activities; however, we need calm weather conditions (winds less than 10 knots) to collect usable photos from the hexacopter. These types of weather conditions are rare in the exposed offshore waters of the Hawaiian Islands. Given few breaks from the prevailing trade winds, we only made a total of 12 flights over cetaceans (spinner dolphins and short-finned pilot whales) on 3 days during HICEAS.

Short-finned pilot whales, including a couple of mother-calf pairs, encountered 175 nautical miles north of Kauai during HICEAS. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Rory Driskell and Amanda Bradford

We were disappointed not only because we didn’t collect very much UAS data during HICEAS, but also because we didn’t have more opportunities to fly the hexacopter. Operating a UAS from a small boat that is rocking around with the large swell of the open ocean, while trying to find the best position to hover over fast-moving animals, is not easy. And we wanted to become good at it, so as to make the most of future opportunities to collect aerial photos of cetaceans.

We agreed that we needed to improve our UAS skills, so we organized a week-long training project off the leeward coast of O’ahu. Leeward O’ahu generally offers protection from the prevailing winds and is regularly used by cetaceans, especially spinner dolphins and, in winter, humpback whales. Our goal with this project was to fine-tune our UAS data collection protocols so that we could gain a better understanding of the factors that produce the highest quality images for evaluating the size and age composition of cetacean groups and the size and body condition of individuals. For example, what are the best camera settings and permitted altitudes for certain species and situations? When is the best time to launch the hexacopter and conserve battery life when individuals in a group are not spending much time at the surface? We were not focused on a particular research question or species, but rather on the UAS operation itself.

Retrieving the hexacopter after a flight over a pair of humpback whales off leeward O’ahu. The unpredictable behavior of the whales at the surface made flying over them surprisingly difficult! Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Kym Yano

A bird’s eye view of the UAS team working off leeward O’ahu. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Kym Yano and Marie Hill.

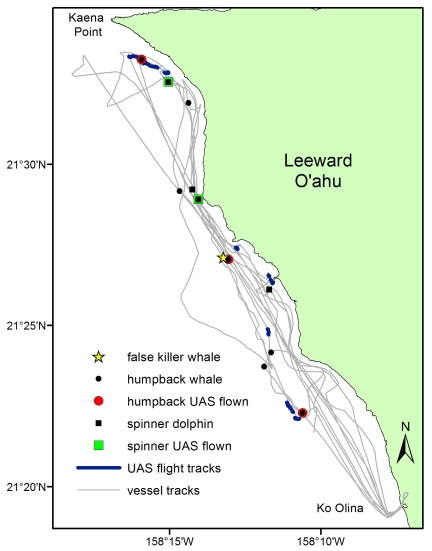

For this project, we conducted daily small-boat surveys off leeward O’ahu between January 8 and January 12, 2018, covering the coastline between Ko Olina in the south and Kaena Point in the north. Cetaceans that we sighted were only approached (and considered “encountered”) if they were outside of restricted airspace and not in the presence of tour operators. Overall, we encountered 12 cetacean groups of 3 species (false killer whales, humpback whales, and spinner dolphins). We considered the potential to fly the hexacopter over each of these groups, which involved evaluating the weather conditions, the behavior of the animals, and the proximity of the group to other vessels. In total, we made 8 flights over 5 groups of 2 species (humpback whales and spinner dolphins).

A large group of spinner dolphins encountered near Kaena Point. A series of such images as the group passes under the hexacopter will allow us to determine the size and age composition of the group. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Marie Hill and Amanda Bradford

We made 5 additional flights not over cetaceans for the purposes of testing camera settings and taking calibration images, where we photograph an object of known size (a 10-foot section of PVC pipe) so that we can determine the amount of error in our cetacean size estimates. In total, 13 flights were made during the week. These flights ranged from 4.2 to 13.8 minutes and totaled 1.9 hours in duration. While our focus was on aerial photography, we did use our hand-held cameras to take photo-identification images during two encounters: 1) a group of false killer whales from the endangered main Hawaiian Islands population that was too spread out and moving too quickly to fly over, and 2) a group of spinner dolphins that we encountered during a period when the wind speed was too high for UAS operations.

A map showing our cetacean UAS pilot study effort and encounters off leeward O’ahu from January 8 to January 12, 2018. We made a total of 13 UAS flights, with 8 of them made over 5 cetacean groups (shown with a colored border around the map marker).

Now that our week-long UAS training project is over, are we UAS pros certain that we’ll get top-notch images every time we fly the hexacopter over cetaceans? Unfortunately, no. In fact, you’d laugh if you saw our humpback whale photos, which were difficult to take because the whales had long dive times and short bouts at the surface. This effort continued to show us that each species, group, and situation is different and that we still have a lot to learn. On a positive note, we made significant progress and are more confident that we can use UAS as a platform to collect meaningful data on cetaceans throughout the Pacific Islands. And, for that reason, we are flying high.

All photos taken under research permit. We’d like to acknowledge the Ko Olina Marina and Ko Olina Community Association for logistical support during the leeward O’ahu UAS training project. Special thanks to Jenna Morris of Dolphin Excursions for alerting us to the presence of main Hawaiian Island false killer whales in the study area.